Antarctica’s coastal waters are facing a grave threat as new research from the University of Colorado Boulder suggests that the acidity of these waters could double by the end of the century. According to the study, the upper 650 feet of the ocean, where a significant amount of marine life resides, could experience over a 100% increase in acidity compared to levels observed in the 1990s. This alarming finding, published in the journal Nature Communications, highlights the potential consequences of ocean acidification on the delicate ecosystems of the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica.

As the world continues to emit high levels of CO2, the oceans serve as a crucial buffer against climate change by absorbing nearly 30% of these emissions. However, this process has a significant downside – the absorbed CO2 dissolves into the seawater, causing it to become more acidic over time. Cara Nissen, the first author of the paper and a research scientist at CU Boulder’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR), emphasizes that human-caused CO2 emissions are at the core of ocean acidification.

The Southern Ocean, which envelops Antarctica, is especially vulnerable to acidification due to several factors. Colder waters tend to absorb more CO2, making the region particularly prone to acidification. Additionally, ocean currents contribute to the relatively acidic conditions in these waters. A computer model developed by Nissen, Lovenduski, and their team simulated the changes in seawater acidity in the Southern Ocean through the 21st century. The results showed that acidification is likely to worsen by 2100, emphasizing the urgent need to reduce emissions globally.

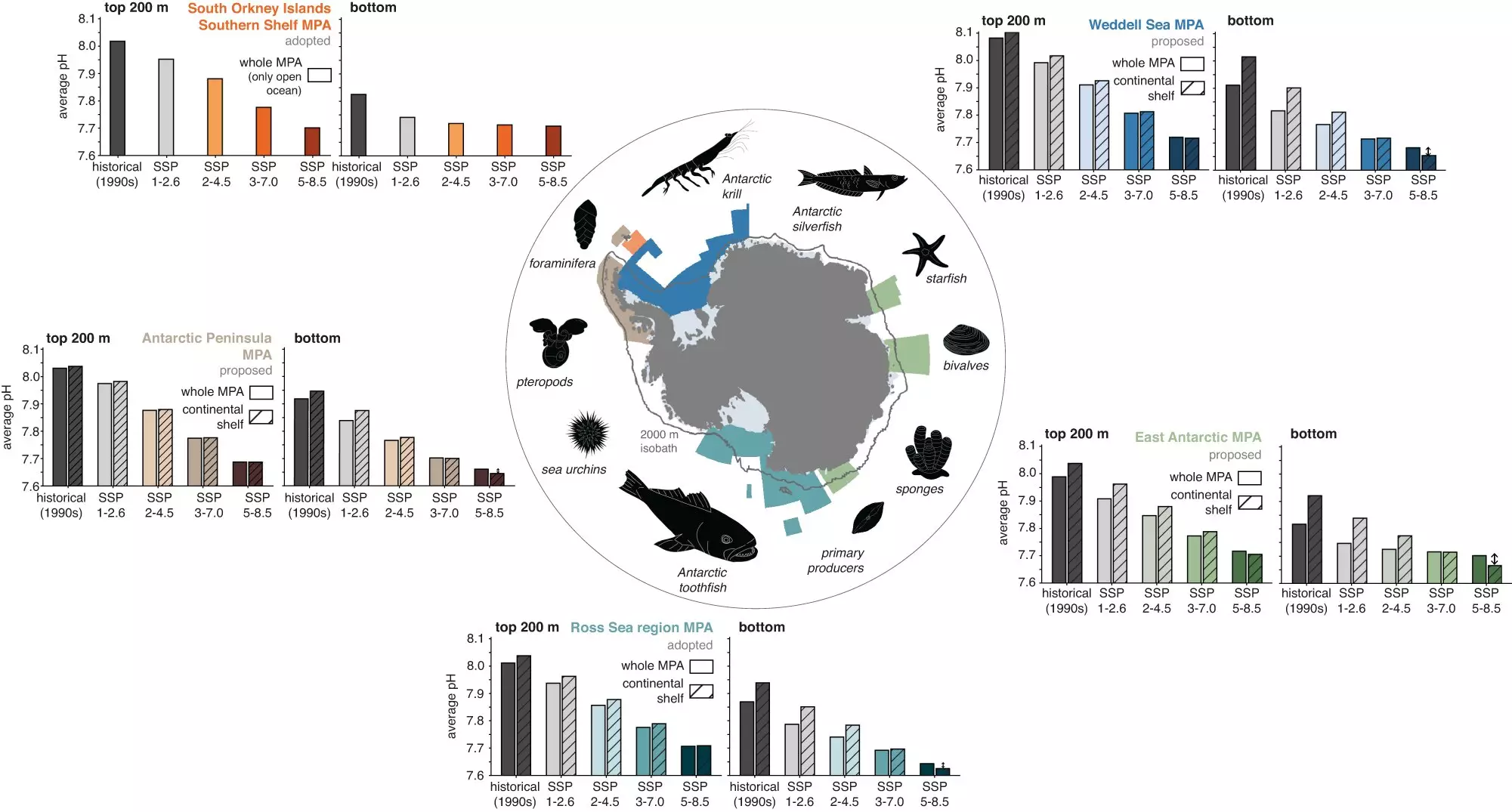

Antarctica’s marine protected areas (MPAs), which limit human activities like fishing to protect biodiversity, are also under threat. Currently, there are two MPAs covering approximately 12% of the Southern Ocean. However, scientists have proposed the designation of three additional MPAs, which would encompass about 60% of the Antarctic Ocean. The researchers’ model demonstrated that both existing and proposed MPAs would experience significant acidification by the end of the century. In the worst-case scenario, where emissions are not reduced, the average acidity of the water in the Ross Sea region, the world’s largest MPA, would increase by 104% compared to the 1990s levels by 2100.

Ocean acidification presents a grave threat to the delicate balance of Antarctic marine ecosystems. Previous studies have shown that phytoplankton, a vital link in the marine food web, struggle to grow or die out in increasingly acidic waters. The shells of organisms like sea snails and sea urchins also weaken in acidic conditions, further disrupting the food web. Ultimately, these changes can have far-reaching consequences for top predators such as whales and penguins, impacting their survival and disrupting the entire ecosystem.

One proposed MPA, the Weddell Sea region, holds particular significance as a potential climate change sanctuary for organisms. The area has the highest levels of sea ice coverage in the Antarctic, which acts as a shield against warming and limits the absorption of CO2 from the air. This natural protection slows down the rate of acidification in the seawater underneath. However, the model suggests that as the planet continues to warm, the sea ice will melt, leading to acidification in the Weddell Sea region that is comparable to other MPAs.

The research findings establish the imperative for swift action to combat ocean acidification. The study suggests that only under the lowest emission scenario, in which CO2 emissions are significantly reduced, can severe acidification of the Southern Ocean be avoided. However, time is running out, and the window for making substantial changes is closing rapidly. It is crucial for society to select an emission pathway that prioritizes sustainability and the preservation of delicate ecosystems like Antarctica.

To protect the marine life and ensure the long-term health of the Southern Ocean, urgent action is needed on a global scale. Governments, organizations, and individuals must work together to reduce CO2 emissions, promote sustainable practices, and preserve biodiversity. The fate of Antarctica’s coastal waters and its iconic inhabitants, from whales to penguins, rests in our hands. It is time to heed the warning signs and take decisive action for the future of these vulnerable ecosystems.

Leave a Reply