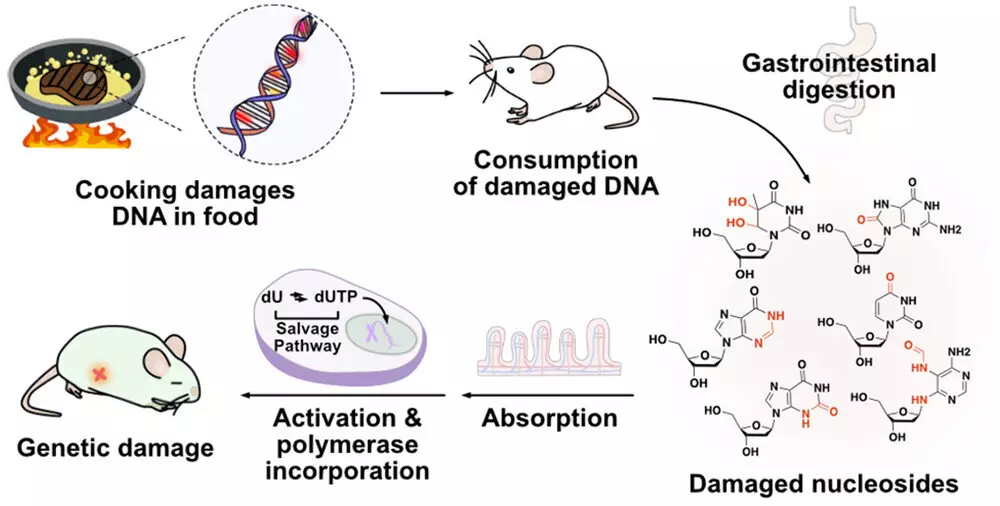

A new study conducted by researchers at Stanford University, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the University of Maryland, and Colorado State University has found a previously unknown reason why foods cooked at high temperatures, such as red meat and deep-fried foods, elevate the risk of cancer. The research discovered that the DNA in food that has been damaged by the cooking process may be absorbed during digestion and incorporated into the consumer’s DNA, placing damage in their DNA, potentially leading to genetic mutations that may eventually cause cancer and other diseases.

The study, published in ACS Central Science, is the first to show that components of heat-marred DNA can be absorbed during digestion and incorporated into the DNA of the consumer, potentially triggering genetic mutations that may eventually lead to cancer and other diseases.

The Findings

The study observed heat-damaged DNA component uptake and increased DNA injury in lab-grown cells and mice. While it’s too soon to say whether this occurs in humans, the findings could have important implications for dietary choices and public health. The study raises concerns about an entirely unexplored, yet possibly substantial chronic health risk from eating foods that are grilled, fried, or otherwise prepared with high heat. The research suggests that building upon these findings could really change our perceptions of food preparation and food choices.

Many studies link the consumption of charred and fried foods to DNA damage, and attribute the harm to certain small molecules that form reactive species in the body. However, those small molecules produced in typical cooking number many thousands of times less than the amount of DNA occurring naturally in foods. For those reactive species to cause DNA damage, they must physically encounter DNA in a cell to trigger a deleterious chemical reaction. In contrast, key components of DNA known as nucleotides that are made available through normal breakdown of biomolecules are readily incorporated into the DNA of cells, suggesting a plausible and potentially significant pathway for damaged food DNA to inflict damage on other DNA downstream in consumers.

The Implications

Many people aren’t aware that foods we eat include the originating organisms’ DNA. The amounts of devoured DNA are not negligible, with a roughly 500-gram beef steak containing over a gram of cow DNA, suggesting that human exposure to potentially heat-damaged DNA is likewise not negligible. The study’s preliminary findings raise questions about a possible chronic health risk from eating foods that are grilled, fried, or otherwise prepared with high heat. The scope of research will need to expand to the long-term, lower doses to heat-damaged DNA expected over decades of consumption in typical human diets, versus the high doses administered in the proof-of-concept study.

The researchers plan on examining cooking methods that simulate different food preparations and testing a broader variety of foods. The team is now looking to delve deeper into these eyebrow-raising, preliminary findings, and they invite the wider research community to build upon them. Overall, the study highlights the importance of considering perplexity and burstiness when it comes to dietary choices and public health.

Leave a Reply