As the effects of climate change continue to unfold, recent research underscores the significant transformation of winter precipitation patterns across the United States. Led by Akintomide Akinsanola from the University of Illinois Chicago, this study analyzes how global warming will influence winter weather by the end of the 21st century. The findings disclose that a higher frequency of “very wet” winters—those in the top 5% of historical precipitation—will be a reality for many Americans. This shift indicates not just an increase in average precipitation but a fundamental change in how winter manifests across various regions.

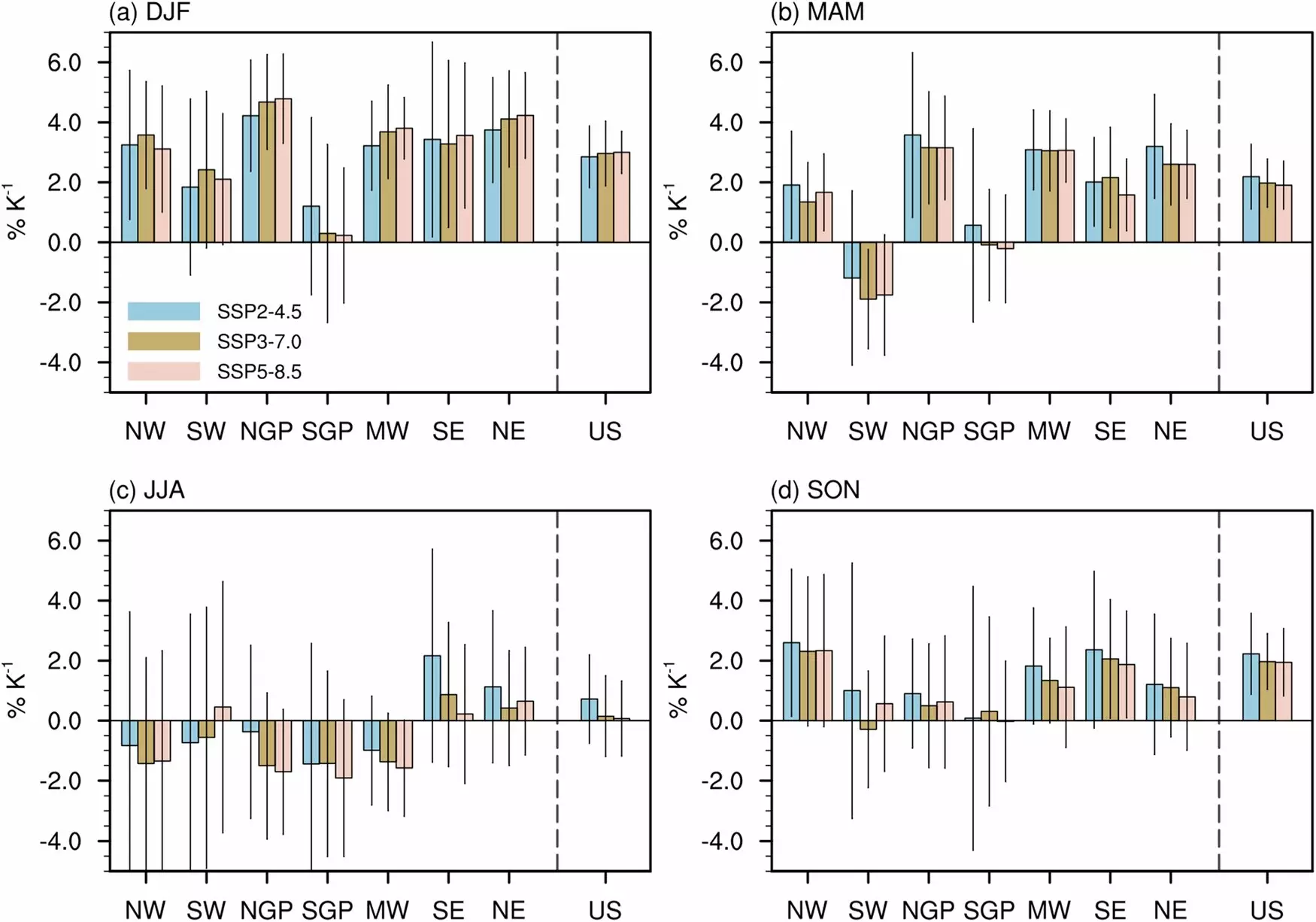

The thorough examination utilized 19 Earth system models to track potential precipitation changes from the late 20th century to the late 21st century. By segmenting the United States into seven distinctive climate subregions, the research highlights discernible trends, revealing that, on average, winter precipitation could rise by approximately 2% to 5% for every degree of warming. Such statistics are distressing, given the broader context of climate variability and increasing extremes in weather.

A significant aspect of the findings is the anticipated transition from snowfall to rainfall in numerous areas, particularly in the Midwest and Northeastern regions. Traditional winter precipitation, which most often comes in the form of snow, will likely be replaced by rain due to rising temperatures. This change raises serious concerns for water resources, agriculture, and flood management, as reduced snowpack will lead to alterations in runoff and water availability during drier months.

Moreover, while the Northwest and Northeast are projected to experience substantial increases in mean winter precipitation, the Southern Great Plains exhibit limited changes in precipitation patterns. Nevertheless, this region may still suffer from extreme dry events, indicating that even when average precipitation appears consistent, the variability can introduce severe challenges in water management and agricultural planning.

The implications of these changing precipitation patterns are multifaceted. Given that winter precipitation will not only increase overall but also intensify in sporadic extreme events, significant upgrades to infrastructure will be required. This includes revising drainage systems and construction codes to withstand the expected uptick in flooding and storm-related damage.

Alykinsanola emphasizes the necessity for proactive planning: “We’re not just talking about mean precipitation; we’re also talking about an increase in extreme events.” This perspective casts a wider net over the discussion of climate change, advocating for increased attention to preparedness and adaptation strategies that account for more than just average predictions.

On top of infrastructure adaptations, the ecological ramifications merit urgent consideration. Many ecosystems depend on seasonal snowfall for hydration, and changes in precipitation type could disrupt these delicate systems. Additional research is required to unravel how plant and animal life will adapt in response to these rapidly shifting winter conditions.

As the urgency for climate research grows, Akinsanola’s future endeavors will delve deeper using high-resolution models that potentially allow for better localized predictions. The anticipation is that assessing compound events—where heatwaves and precipitation extremes overlap—will provide vital insights into the cascading effects of climate change on communities and ecosystems across the nation.

Cooperating with institutions such as the Environmental Science Division at Argonne National Laboratory, Akinsanola’s work represents a critical frontier in understanding climate dynamics. Addressing not just statistical changes but real-world implications ensures that the urgency of the climate crisis is matched with actionable knowledge.

The findings presented by Akinsanola and his team should serve as both a warning and a call to action. As wetter winters and altered precipitation patterns become increasingly likely, communities, policymakers, and scientists must collaborate to develop strategies for resilience. Preparing for the inevitable changes in our climate is not merely an academic exercise; it is essential for the sustainability and safety of future generations. The time to act is now.

Leave a Reply