Mosquitoes are one of the deadliest animals on the planet, causing millions of deaths each year due to the diseases they transmit. We know that mosquitoes are attracted to human body odor, but how do they find us from such long distances? In a recent study published in the journal Current Biology, researchers used an outdoor testing arena in Zambia to understand how mosquitoes locate and choose human hosts over a large and more realistic spatial scale.

The Study

Researchers from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s Malaria Research Institute and Macha Research Trust built a 1,000 m3 testing arena in Choma District, Zambia, containing a ring of evenly spaced landing pads that were heated to human skin temperature (35ºC). Each night, the researchers released 200 hungry mosquitoes into the testing arena and monitored their activity using infrared motion cameras. Specifically, they took note of how often mosquitoes landed on each of the landing pads (which is a good sign that they’re ready to bite).

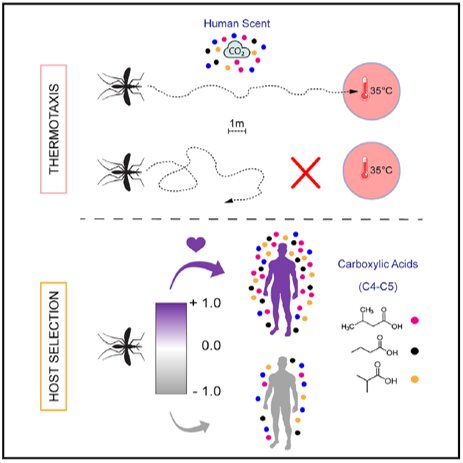

First, the team compared the relative importance of heat, CO2, and human body odor for attracting mosquitoes. They found that mosquitoes were not attracted to the heated landing pads unless they were also baited with CO2, but human body odor was a more attractive bait than CO2 alone.

Next, the team tested the mosquitoes’ choosiness. To do this, they had six people sleep in single-person tents surrounding the arena over six consecutive nights, and they used repurposed air conditioner ducting to pipe air from each tent—containing the aromas of its sleeping occupant—onto the heated landing pads. As well as recording the mosquitoes’ preferences, the researchers collected nightly air samples from the tents to characterize and compare the airborne components of body odor.

“These mosquitoes typically hunt humans in the hours before and after midnight,” says senior author and vector biologist Conor McMeniman, assistant professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute. “They follow scent trails and convective currents emanating from humans, and typically they’ll enter homes and bite between around 10 PM and 2 AM. We wanted to assess mosquito olfactory preferences during the peak period of activity when they’re out and about and active and also assess the odor from sleeping humans during that same time window.”

The team identified 40 chemicals that were emitted by all of the humans, though at different rates. People who were more attractive to mosquitoes consistently emitted more carboxylic acids, which are probably produced by skin microbes. In contrast, the person who was least attractive to mosquitoes emitted less carboxylic acids but approximately triple the amount of eucalyptol, a compound found in many plants; the researchers hypothesize that elevated levels of eucalyptol may be related to the person’s diet.

The researchers were surprised by how effectively the mosquitoes could locate and choose between potential human meals within the huge arena. “When you see something moved from a tiny laboratory space where the odors are right there, and the mosquitoes are still finding them in this big open space out in a field in Zambia, it really drives home just how powerful these mosquitoes are as host seekers,” says analytical chemist Stephanie Rankin-Turner, a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the study’s other first author.

Conclusion

Human body odor is critical for mosquito host-seeking behavior over long distances. The research team also identified specific airborne body-odor components that might explain why some people are more attractive to mosquitoes than others. The study’s findings could help develop new ways to prevent mosquito-borne diseases and better protect people from mosquito bites.

Leave a Reply