Plants derive their carbon from the atmosphere and use it to synthesize organic compounds through photosynthesis and water. Terrestrial ecosystems have been absorbing about 32% of CO2 emissions produced by human activities for the past 60 years. However, the question of whether terrestrial vegetation can continue to function as a carbon sink in a changing climate is a crucial issue in climate science and of great political importance. Climate change has triggered various feedback loops, processes that either amplify or reduce climate change. The carbon system feedback loops are difficult to measure and model and are a significant source of uncertainty in climate forecasts.

The Impact of Droughts on Carbon Sinks in Tropical Areas

Previously, existing literature indicated that terrestrial carbon sinks would only be significantly affected by high to very high increases in global warming. A team of researchers led by Sonia Seneviratne, Professor for Land-Climate Dynamics at ETH Zurich, found that terrestrial ecosystems may be less resilient to climate change than previously thought. The researchers found that tropical carbon sinks were becoming increasingly vulnerable to water scarcity. Droughts have had a growing influence on the carbon cycle in the tropics, with vegetation absorbing less CO2 during drought events. This effect is not captured by most climate models. The observed change is based on a known feedback loop; plants stop absorbing CO2 to avoid water loss under hot and dry conditions. In addition, there can be an increase in plant mortality and fire events, which leads to the additional release of CO2 into the biosphere. If such conditions occur more frequently, it can lead to a reduction in the terrestrial CO2 sink, resulting in a further increase in global warming.

In 2018, Seneviratne’s team demonstrated on a global scale how stressed ecosystems absorb less carbon during severe droughts and how the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere increases significantly in dry years. The growth rate of atmospheric CO2 varies from year to year in line with terrestrial water availability. The researchers’ greatest challenge was to determine where droughts were occurring worldwide. Sophisticated satellite observation of Earth’s water reservoirs has since enabled this to be determined more accurately.

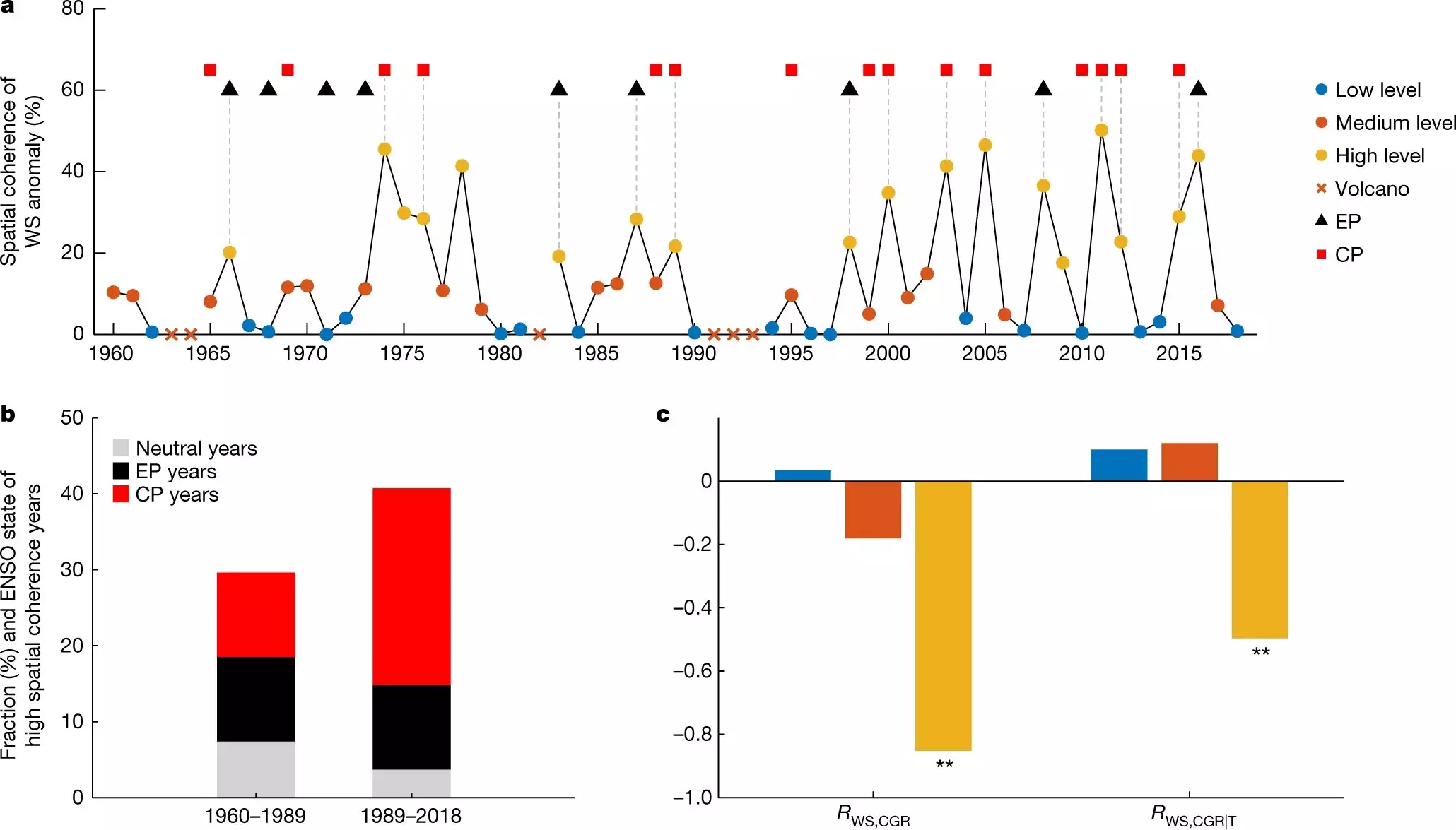

The researchers wanted to find out whether there was a change in the relationship between water availability and CO2 growth rate over time. The researchers were able to demonstrate that the coupling between tropical water availability and CO2 growth rates intensified in the 30-year period between 1989 and 2018 when compared to the period from 1960 to 1989. Tropical water scarcity has become an increasingly limiting factor shaping the annually fluctuating carbon cycle and its feedback loops.

The results of the study are concerning to Seneviratne, as they highlight a process that could intensify global warming. She wants to investigate what has caused the increasingly severe tropical droughts and higher sensitivity of tropical ecosystems and why climate models are not capturing these features. One possible explanation could be changes in the spatial characteristics of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), as the researchers write in their study. However, Seneviratne urges caution against jumping to conclusions. “Our study looked at historical data—not directly at projections. The results provide no forecasts,” the climate researcher stresses.

The increased role of water limitation not reflected in climate models could mean that plant carbon uptake and the resilience of vegetation to droughts have been overestimated. “This would affect the assessment of climate targets and measures and make it necessary for us to recalculate the global carbon budget for the remaining emissions,” says Laibao Liu, a postdoctoral researcher in Seneviratne’s group and first author of the study. The climate models must first of all be able to adequately take into account the consequences of droughts on the carbon cycle. “Only then can we make more accurate projections for future carbon sinks on land,” Sonia Seneviratne says.

Seneviratne expects many regions with extensive vegetation, especially the Amazon in the tropics, to be more affected by droughts as temperatures rise. Any increase in the effect of droughts on the carbon cycle would not bode well.

Leave a Reply