The notion that Mars might have once cradled a vast ocean continues to inspire scientific inquiry and debate. Recent findings from China’s Zhurong rover add new layers to this ongoing investigation. These discoveries not only reinforce existing theories about ancient Martian water bodies but also reignite skepticism regarding the interpretation of geological features gleaned from the Martian surface. This article delves into the implications of the findings while also weighing the concerns posed by critics of the research.

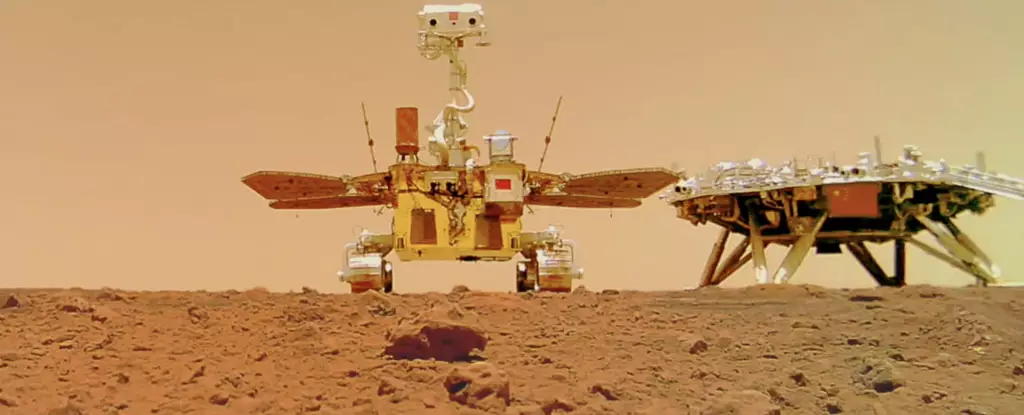

Launched in 2021, China’s Zhurong rover successfully landed in the Utopia Planitia region of Mars. This mission marked a significant milestone in China’s space exploration endeavors and positioned the rover in a locale that previous studies suggested may have hosted water eons ago. Since its landing, Zhurong has meticulously collected geological data, returning insights that suggest characteristics historically associated with an ocean. Research published in *Scientific Reports* showcases some of these compelling indicators including “pitted cones” and “polygonal troughs,” which evoke images of ancient water interaction with the Martian landscape.

Researchers involved in the mission posited that these formations could represent past sedimentary processes linked to a once-thriving ocean. The presence of seabed-like structures raises exciting possibilities about Mars’ climatic history and its geological evolution over billions of years. Team lead Bo Wu articulated the potential of these discoveries to redefine our understanding of the Red Planet, though he tempered expectations by asserting that definitive proof remains elusive.

Estimating the timeline of Martian geological events, researchers suggest that water pooled on the planet’s surface nearly 3.7 billion years ago before eventually freezing and eroding into the formations we observe today. This hypothesis posits not just the existence of water but also a dynamic interplay of environmental factors, such as temperature fluctuations and tectonic activity. However, Bo Wu cautioned that while the evidence is suggestive, it does not conclusively establish the existence of an ocean.

One of the intriguing aspects of this research is its reliance on a combination of rover data and Earth-based satellite observations. The apparent shoreline formations in the vicinity of Zhurong’s landing site could indicate that, at one time, Mars experienced conditions conducive to harboring large bodies of water. Such claims resonate with a growing body of literature advocating for the idea that Mars was once significantly wetter than it is today.

However, not all scientists are convinced by these assertions. Benjamin Cardenas, an expert in Martian geology from Pennsylvania State University, raises important caveats. He argues that the erosive forces of Martian winds over billions of years could obliterate crucial geological evidence of a shoreline. According to his analysis, even the slow rates of erosion observed on Mars could potentially mask the remnants of ancient coastlines. Cardenas viewed the evidence presented by the Zhurong team with healthy skepticism, advocating for a more nuanced interpretation of the geological data.

Moreover, Cardenas alludes to a broader concern: the methodology used in the study may not adequately account for the complexities of Martian geological processes, including ongoing erosion and sediment displacement. He underscored the importance of rigorous scientific rigor in distinguishing between geological features that could result from ancient aquatic environments versus those shaped by wind and impact erosion.

Despite the contention surrounding the recent findings, the implications of discovering substantial evidence for a Martian ocean are profound. Such an understanding could fundamentally alter humanity’s perspective on life’s potential across the solar system. If Mars was indeed once an oceanic world, it begs the questions of whether life could have originated there or if Earth remains unique in its capacity to support life.

As the community of planetary scientists continues to assess these findings, the quest for truth in Martian exploration remains ongoing. Future missions—ideally those capable of returning samples to Earth—may be necessary to finally resolve the long-standing debate over Mars’ aqueous history. Until then, the interplay between emerging evidence and healthy skepticism ensures a vibrant and ongoing dialogue in the field of astrobiology, shaping not only our understanding of Mars but also of life beyond Earth.

Leave a Reply