The proliferation of microplastic contamination in marine environments is a pressing global issue that demands immediate attention from both scientists and policymakers. As research efforts intensify, experts at Flinders University are pinning their hopes on new methods to evaluate and address this escalating pollution crisis. Their recent study, published in the esteemed journal *Science of the Total Environment*, focuses on the interaction between microplastics and marine plankton, particularly zooplankton. This research not only sheds light on the ubiquitous presence of microplastics but also explores innovative testing methodologies aimed at mitigating their impact.

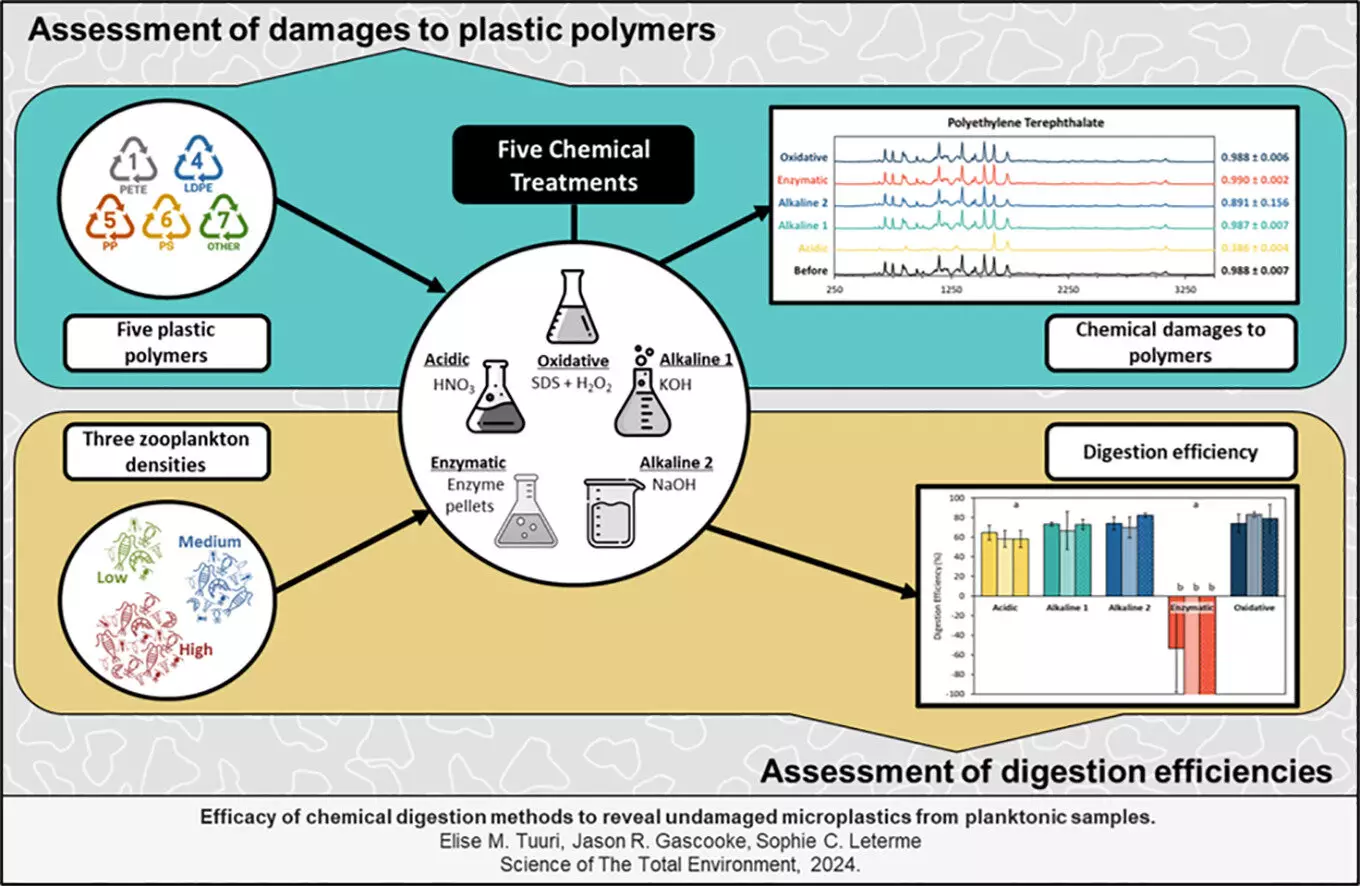

Flinders University’s researchers implemented a structured experimental design to investigate how distinct chemical digestive aids influence common plastics when they coexist with varying zooplankton concentrations. The study utilized cultured zooplankton maintained in a controlled laboratory setting, allowing scientists to systematically assess the effects of five different digestive processes—acidic, alkaline (two types), enzymatic, and oxidative—on several prevalent plastics, including polyethylene and polystyrene. By applying these methodologies, the researchers were able to gauge the degree of damage inflicted on the microplastics, thus providing crucial insights into their resilience and degradation in marine environments.

Elise Tuuri, a Ph.D. candidate involved in the study, highlighted the substantial consequences that microplastic pollution has on marine ecosystems. Research indicates that microplastics, defined as plastic particles smaller than 5mm, contaminate various marine organisms, notably fish and shellfish, which raise concerns regarding food safety for human consumption. The findings underscore a critical intersection between environmental health and public health, advocating for renewed investigation into the bioaccumulation of microplastics within marine food webs.

The research underscores a grim reality: plastic production has skyrocketed from a mere 2 million metric tons in 1950 to an alarming 380 million metric tons in 2015, with predictions suggesting that production levels could triple by 2050. This exponential growth has established plastic waste as the principal form of anthropogenic marine litter, accumulating in deep-sea and shoreline environments alike. The ubiquity of microplastics emphasizes an urgent need to formulate effective management strategies that address their proliferation, particularly as they continue to infiltrate our ecosystems undetected.

Professor Sophie Leterme, a co-author of the study, advocates for the need to refine the assessment methods for microplastic concentrations as a tool to better understand their implications for both health and environment. By collecting and analyzing abundant microplastic data, researchers can devise targeted strategies aimed at reducing marine pollution. A deeper understanding of how microplastics interact with marine organisms, particularly sensitive species like zooplankton, will ultimately enable a more comprehensive strategy for mitigating the ecological damage caused by plastic pollution.

As the urgency of addressing plastic waste escalates, research such as that from Flinders University may pave the way for innovative solutions. It is imperative for the scientific community and global citizens alike to remain vigilant and proactive in combating plastic pollution to safeguard our oceans and the myriad forms of life that inhabit them.

Leave a Reply