Water is an essential compound that covers over 70% of the Earth’s surface. Despite its ubiquitous presence, scientists have identified over seventy anomalous properties of water that are difficult to verify experimentally. One of the reasons is the inability to study water between 160 K and 232 K (-113 °C to -41 °C), a subzero temperature range known as “no man’s land,” where water crystallizes so fast that scientists have been unable to study its properties. However, researchers at EPFL have discovered a new method to study “no man’s land” water that can help unravel the mysteries of water.

New Method to Study “No Man’s Land” Water

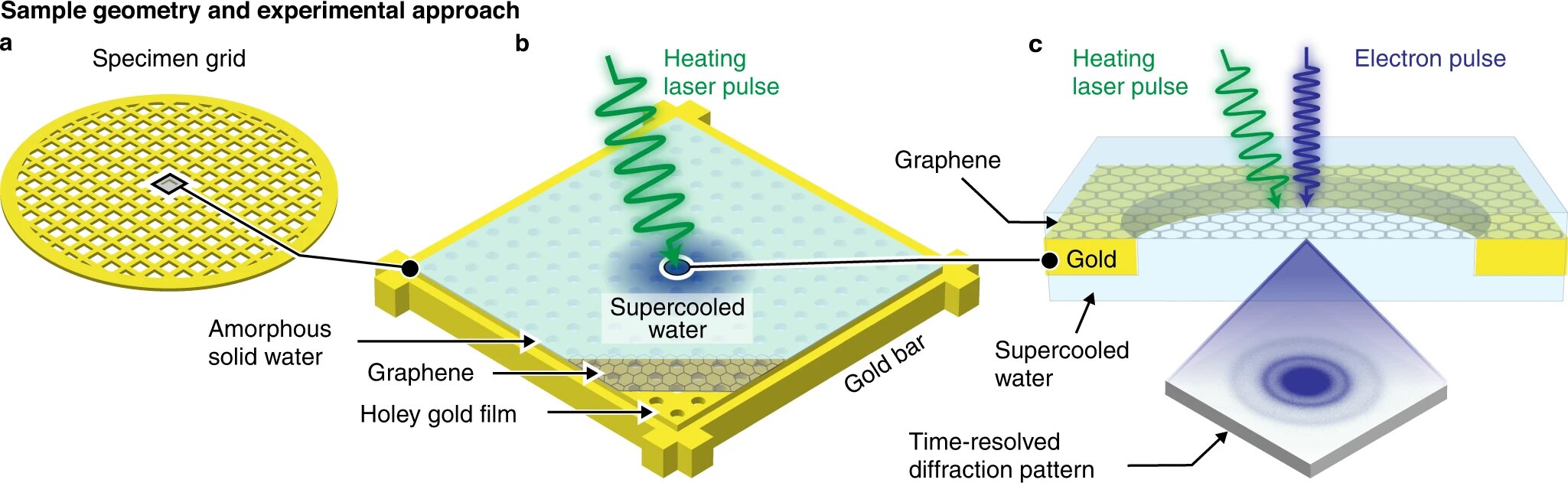

Scientists at EPFL have developed a way to rapidly prepare deeply supercooled water at a well-defined temperature and probe it with electron diffraction before it can crystallize. Historically, the inability to access “no man’s land” has prevented scientists from unriddling the anomalous nature of water, but the breakthrough method can now change that. The team developed a specialized time-resolved electron microscope in their lab to perform the experiments. They cooled a layer of graphene to 101 K and deposited a thin film of amorphous ice. They then locally melted the film with a microsecond laser pulse to obtain water in “no man’s land” and captured a diffraction pattern with an intense, high-brightness electron pulse.

The researchers found that as water is cooled from room temperature to cryogenic temperatures, its structure evolves smoothly. At temperatures just below 200 K (about -73 °C), the structure of water begins to look like that of amorphous ice, unlike the tidy crystalline ice we are usually familiar with. The structure’s smooth evolution allowed the researchers to narrow down the range of possible explanations for the origin of water anomalies. Professor Ulrich Lorenz at EPFL’s School of Basic Sciences said that “the fact that the structure evolves smoothly allows us to narrow down the range of possible explanations for the origin of water anomalies. Our findings and the method we have developed bring us closer to unriddling the mysteries of water. It is difficult to escape the fascination of this ubiquitous and seemingly simple liquid that still has not given up all of its secrets.”

Why Study “No Man’s Land” Water?

Why would anyone want to cool water to such low temperatures? Because when water is cooled way below its freezing point, it becomes “supercooled” with unique and fascinating properties. For example, under certain conditions, it can remain in liquid form but can freeze instantly when disturbed or exposed to certain substances. Supercooled water is obtained by taking liquid water and cooling it below the freezing point while using tricks to prevent it from crystallizing or at least slowing this process down. However, even with these tricks, crystallization in “no man’s land” is still too fast.

Water’s anomalous properties have several theories trying to explain them, but verifying them experimentally is difficult. By studying “no man’s land” water, scientists can better understand how water’s anomalous properties arise. Water’s unique properties have shaped the Earth’s composition and geology, regulate its climate and weather patterns, and are at the foundation of all life as we know it.

Scientists at EPFL have discovered a new method to study “no man’s land” water, which could help unravel the mysteries of water. The breakthrough method can rapidly prepare deeply supercooled water at a well-defined temperature and probe it with electron diffraction before it can crystallize. The researchers found that as water is cooled from room temperature to cryogenic temperatures, its structure evolves smoothly. The structure’s smooth evolution allowed the researchers to narrow down the range of possible explanations for the origin of water anomalies. By studying “no man’s land” water, scientists can better understand how water’s anomalous properties arise, which have shaped the Earth’s composition and geology, regulate its climate and weather patterns, and are at the foundation of all life as we know it.

Leave a Reply