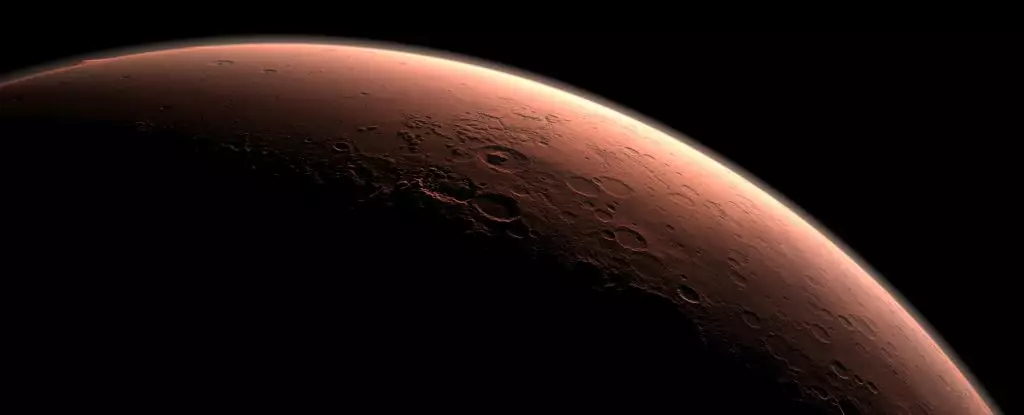

Mars, a planet that has captured human imagination for centuries, remains an enigmatic subject of exploration. Despite numerous missions to the red planet, scientists have not yet secured concrete evidence of life. However, the Viking landers—pioneering spacecraft that landed on Mars in the 1970s—may have skimmed the surface of something more profound than anyone initially realized. Recent assertions by astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch have brought new scrutiny to the experiments conducted on Mars nearly five decades ago. These reflections call into question whether our approach may have inadvertently buried potential evidence of extraterrestrial life.

In 1976, the Viking landers made history by executing the first successful landings on Mars with the goal of assessing the planet’s environment. Scientists devised several innovative experiments aimed at identifying biosignatures—molecular indicators of life—within Martian soil. The Viking missions produced an array of results, some of which suggested signs of life, though none were conclusive. A critical experiment—the gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer (GCMS)—detected chlorinated organics, but early interpretations attributed these findings to contamination from Earth. This misinterpretation highlights a significant oversight in our understanding of the Martian ecosystem.

What complicates the scientific narrative further is that contemporary research has confirmed that chlorinated organics can form through non-biological processes on Mars. Therefore, the evidence of past or even surviving life is left tantalizingly ambiguous. Did the Viking instruments truly fail to detect living organisms, or did they obliterate the very signatures we sought? Schulze-Makuch posits that this notion could hold considerable merit.

The Viking experiments were bold, but with innovation came risk. One of the core tasks involved heating soil samples, a method intended to segregate various materials for analysis. In a regrettable twist, this process may have incinerated any microbial life that existed within those samples. Schulze-Makuch highlights another dimension to this debate: the labeled release and pyrolytic release experiments, which infused Martian samples with liquids to ascertain metabolism and photosynthesis activity.

At the time, scientists assumed that Martian life would closely mimic life on Earth, requiring liquid water for sustenance. However, adjusting our understanding of life to account for extremophiles—organisms that thrive in harsh, arid environments—may alter our perspective. Mars is inherently dry, and any organisms that had evolved to endure such conditions could have suffered under additional water exposure. One could liken it to attempting to rescue a stranded person in a desert by submerging them in an ocean—such actions could prove detrimental rather than life-saving.

Interestingly, the results from the pyrolytic release experiment showed that signs of life appeared more robust when conducted without introducing water. These findings raise intriguing questions about our experimental design: could we have overlooked potential signals of life due to our preconceived assumptions about hydration?

The Call for Renewed Exploration

Reflecting on the lessons gleaned from Viking missions, Schulze-Makuch calls for future endeavors to approach Mars with a fresh perspective—one that accommodates the possibility of life forms that adapt to dryness, potentially even utilizing hydrogen peroxide as a survival strategy. His assertions suggest a profound rethinking of our methodologies in the search for life on Mars, advocating for missions explicitly focused on this pursuit.

Given recent findings from Martian missions, the synopsis of the Viking explorations may require more than just critical analysis—it beckons a renewed commitment to exploration. The focus should shift toward employing advanced technologies and techniques that account for the unique ecological framework on Mars. Investigating the shortfalls of past missions may not only shed light on the Viking landers’ legacy but also lay the groundwork for future missions aimed at unraveling the secrets of Martian biology.

While we have yet to unearth definitive evidence of life on Mars, the Viking missions provide a crucial framework for understanding what may be possible. Those initial explorations suggest that we stand at the brink of discovery, with more questions than answers. As our technology and understanding advance, the potential for finding Martian life—however improbable it may seem—remains ripe for exploration, beckoning scientists toward a future filled with possibilities.

Leave a Reply