New research from the University of Canterbury School of Mathematics and Statistics in New Zealand has found that seismic signals can be used to track pyroclastic flows, which are the most deadly volcanic hazard in the world. These flows result from volcanic eruptions and can travel at speeds of up to 500 kmh (310 mph). Pyroclastic flows caused the catastrophic eruption at Whakaari White Island in 2019, which led to the death of 22 people, and an earlier eruption on Mt. Tongariro in 2012, which resulted in the closure of the Tongariro Alpine Crossing. More than half of all volcano-related deaths around the world are caused by pyroclastic flows.

Seismic Signals Help in Real-Time Hazard Assessments

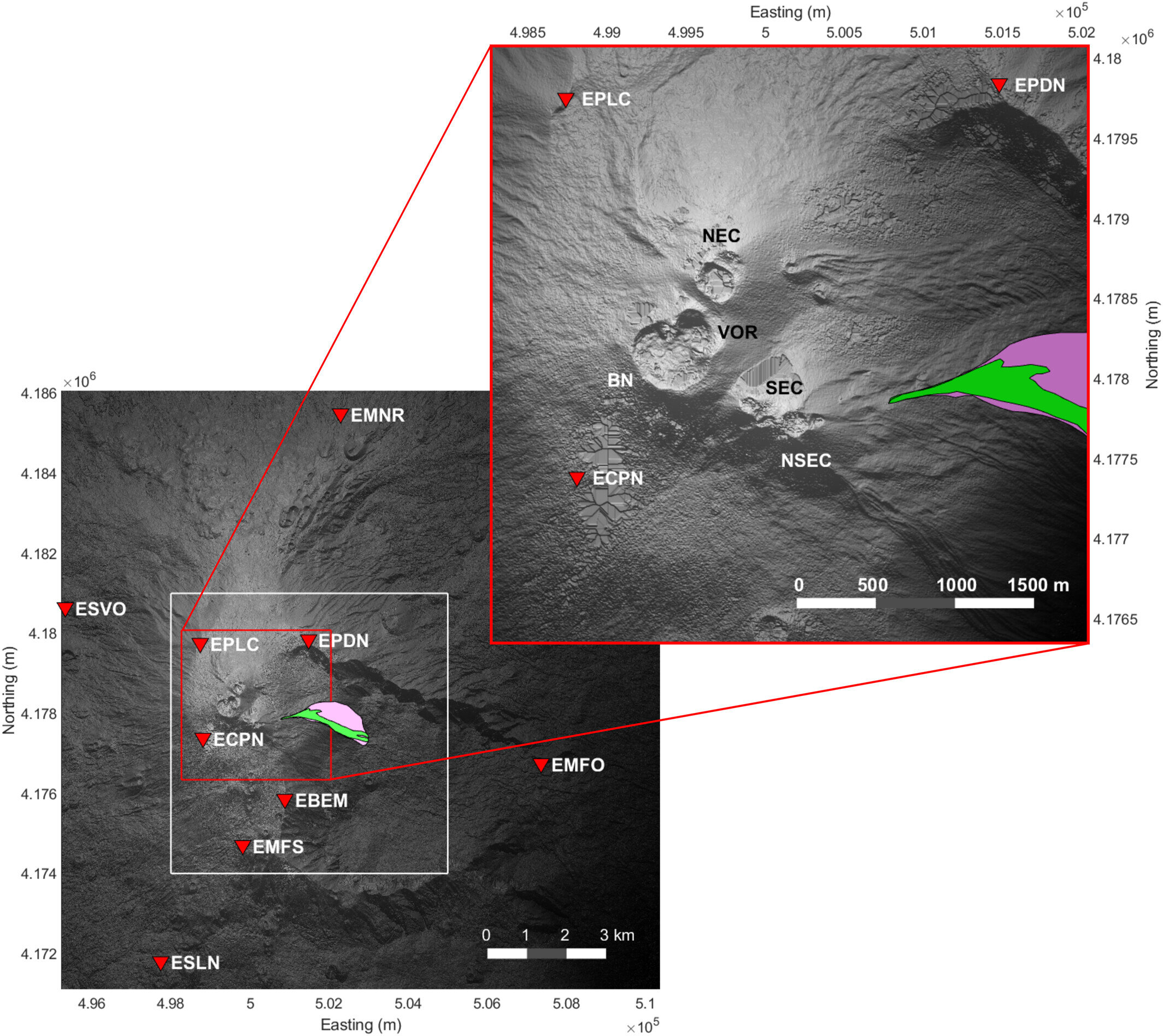

Dr. Leighton Watson, a lecturer at the University of Canterbury, revealed that these flows are extremely difficult to study because they are sudden, fast-moving, and dangerous. The opaque gas cloud produced by these flows makes it impossible to see the internal flow dynamics. However, Dr. Watson used seismic data from a permanent monitoring network at Mt. Etna, Italy, to track a pyroclastic flow that occurred in February 2014. He found that the pyroclastic flow, as it travels down the volcano, pushes onto the Earth’s surface, producing seismic waves. These signals can be used to track the flow and model its flow path in real-time, which can help with hazard assessments for future eruptions.

By analyzing how seismic signals decrease in strength as they move away from the pyroclastic flow, the source of the vibrations can be located and tracked over time. Dr. Watson says that the extreme hazard posed by pyroclastic flows demands an improvement in monitoring capabilities. The findings could be applied to volcanoes in New Zealand such as Ruapehu, Tongariro, and Taranaki. Since all New Zealand volcanoes can produce pyroclastic flows, better monitoring capabilities could improve safety.

Using Seismic Signals to Better Understand and Monitor Volcanic Hazards

Dr. Watson hopes to carry out further research in New Zealand using seismic signals to track lahars (mudflows composed of rock, debris, and water), as well as pyroclastic flows. A lahar from Ruapehu destroyed a bridge over the Whangaehu River causing a train derailment in the 1953 Tangiwai disaster that killed 151 people. The ultimate goal is to better understand and monitor volcanic hazards to save lives. This is especially important since volcanoes are often shrouded in cloud, and eruptions can occur at night when cameras are ineffective.

Dr. Watson has previously shown that sound waves can be used to detect mountain avalanches along the Milford Road and is currently working on monitoring avalanche activity in Mount Cook Aoraki National Park.

Leave a Reply