Researchers from the University of Helsinki and the University of Eastern Finland have found that a particular genus of microbe, commonly found in wet and boggy environments, could play a critical role in Parkinson’s disease. The researchers discovered that the microbe generates compounds that activate proteins inside brain cells to form toxic clumps. These findings build on an earlier investigation that showed the severity of Parkinson’s disease in volunteers increased with concentrations of Desulfovibrio bacterial strains in their feces.

The Study

The researchers conducted a study to identify the potential path from the presence of Desulfovibrio bacteria in genetically edited worms to physical changes in the brain that coincide with Parkinson’s disease. The study’s purpose is to improve early detection of the disease in humans or even slow its development. The researchers found that the presence of harmful Desulfovibrio bacteria in individuals’ guts could be screened, and the bacteria could be targeted by measures to remove them, potentially alleviating and slowing patients’ Parkinson’s symptoms.

Researchers have sought an explanation for why some people develop a loss of fine motor control as they age, even since James Parkinson, an English physician, first described the disease as a neurological condition some two centuries ago. Parkinson’s disease causes small inclusions known as Lewy bodies to accumulate in the cells of specific regions of the brain. Investigations of these microscopic clumps of material have revealed that they are mainly made up of a protein called α-synuclein, which is typically involved in the release of neurotransmitters. The reason for α-synuclein’s aggregation is not entirely clear, but it is suspected that the very presence of these concentrations, called protofibrils, can’t be great for the healthy functioning of nerve cells.

The study revealed that environmental conditions are the probable cause of α-synuclein’s aggregation. Studies show that the kinds of bacteria we harbor in our guts predict the likelihood of an individual having, or at least developing, Parkinson’s symptoms. Saris’s 2021 study provides evidence of a single prime suspect that researchers can focus on.

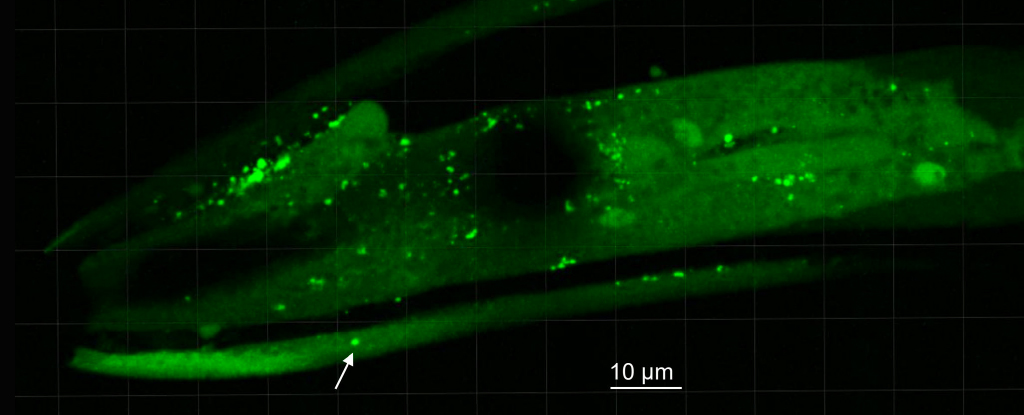

The researchers took fecal samples from ten patients with Parkinson’s disease and their healthy spouses and isolated any strains of Desulfovibrio present. The extracted test microbes were then fed to transgenic specimens of Caenorhabditis elegans nematode, which had been modified to express human α-synuclein. A statistical analysis based on microscopic observations of the nematodes’ heads revealed those fed Desulfovibrio were indeed far more likely to produce α-synuclein clumps, and those clumps were more likely to be much larger. Desulfovibrio strains collected from Parkinson’s patients were also better at aggregating the proteins in C. elegans than those collected from their partners.

The same experiment could not be replicated in a sample of healthy people. However, studies will continue to investigate ways Desulfovibrio in our guts might spark the formation of α-synuclein aggregates that could migrate through the body. In time, therapies that target the digestive system and its surrounding nerves may manage the progress of Parkinson’s disease instead of the brain.

Leave a Reply